By Riley Weeks. This is Part One in a three-part series about how pollution affects the Salish Sea, the people and animals that rely on it, and what RE Sources and other community advocates are doing about it.

A large part of environmental advocacy is speaking up for those without a voice, or at least ones we can’t understand yet. Although we know that trees can communicate with one another and that countless animal species are way more intelligent than most humans give them credit for, we still haven’t found a way to broadly make the legal case that plants and animals should have rights, too.

It’s not just humans who face the repercussions from unregulated, unmonitored pollutants. Pollution also impacts the plants and animals that call the Salish Sea home.

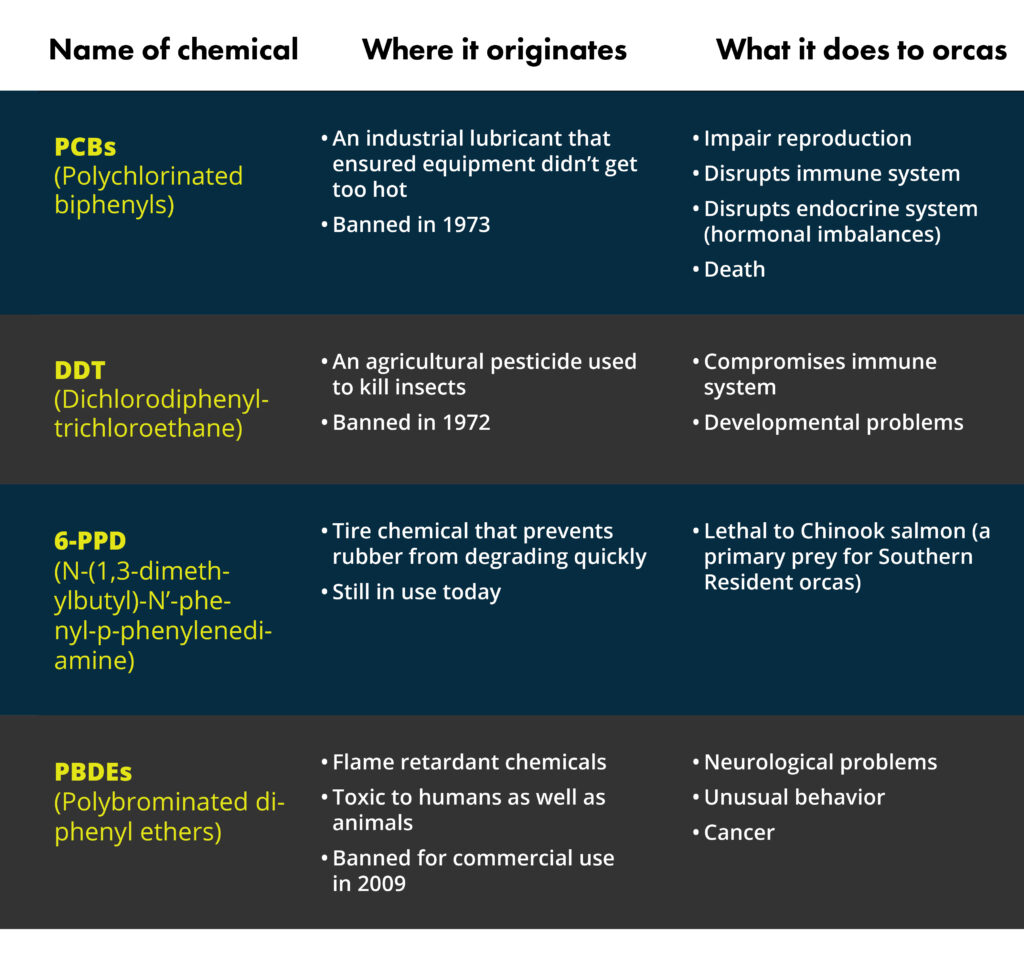

One pod of whales in particular is facing the brunt of the effects caused by pollution. Orcas are top predators and can consume up to 385 pounds of Chinook salmon every day. Chemicals like PCBs, DDT, PFAs, 6-PPD, PBDs all bioaccumulate up the food chain, compounding the negative impacts of these toxicants.

Deborah Giles, the science and research director at Wild Orca, has been learning from and advocating for Southern Resident orcas since 2005. Giles, her research and life partner Jim, and her trained scent-dog Eba all work together to collect fecal samples from the Southern Residents. When the team receives word that the orcas are coming back into the Salish Sea through the Strait of Juan de Fuca, they jump into action.

They follow the pod downwind and from a long ways away to ensure the whales are not disturbed. Eba positions her body towards any whiff of orca poop, and the boat and team follow her lead.

“We use beakers on the end of a pole to scoop scat samples out of the water,” Giles said.

After that, the team centrifuges them on the boat to pull off as much seawater as possible and then freezes them. The samples are labeled and frozen at the Wild Orca labs in Friday Harbor. Once enough samples have been collected, they are sent to the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance to be tested.

Using public transportation and doing away with single use items are concrete ways that the public can help to support the health of Southern Resident orcas, according to Giles.

RE Sources, too, is working towards protecting the Salish Sea and facilitating orca recovery through our Salish Sea-focused programs. Our staff are working to find more affordable ways to collect pollution data locally, and use what we find to push government entities to do more monitoring to find the source of those pollutants. We look holistically at toxicants that enter the Salish Sea, and work collectively to mitigate their impacts.

Toxicants, vessel impacts and lack of prey are three major threats to Southern Resident orcas. If an orcas’ ability to eat and hunt are impaired, they start to use up their blubber stores to stay alive. Unfortunately, their fat is where all the accumulated chemicals are stored. Chemicals also make their way in high concentrations to a nursing calf through their mother’s milk, and can be lethal.

Orcas may not speak in a language that humans can understand, but we can look to their resilience and learn from their community building.

“When I start to feel like my optimism is flagging, I look to them [the whales] and I see that they’re not giving up, and so how dare I give up,” Giles said.