The killer whale, or orca, is an iconic figure of the Pacific Northwest. Up and down Washington’s coast you will find murals, stickers, license plates, sculptures, t-shirts and more dedicated to orcas. The whale watching industry supports over $216 million of economic activity per year in Washington state. Locals and tourists alike just cannot get enough of them.

Often when we hear about orcas in the news, it’s about the endangered Southern Residents population and their decline. Yet, earlier this year, headlines suggested killer whale numbers were on the rise. So which is it? The confusion stems from the fact that Washington’s waters are home to not one but three distinct types of killer whale.

One species, many cultures

Though all orcas around the world are one species, they are divided into separate groups, or ecotypes. Like human populations, orcas have distinct cultures, languages and preferred tasty snacks. Here in Washington we have three distinct groups: The mysterious offshore clan, the famous Southern Resident killer whales, and the Biggs.

There is very little known about offshore killer whales. They are said to eat great white sharks, solidifying their spot as top predators. They are rarely seen and not much is known about their population.

The Southern Resident pods are the most iconic and well-publicized groups. There are three distinct pods that historically call the Washington waters home. They are J, K and L pods. The Southern Resident population has shown an overall declining trend since 1995, falling to only 75 whales as of July 2023. They are federally listed as endangered in the U.S. and Canada. They almost exclusively eat Chinook salmon — which due to overfishing, declining river health, and dammed rivers are an imperiled species themselves. This makes it harder and harder for the Southern Residents to get enough to eat, even leading to signs of malnourishment symptoms like “peanut head”. On top of declining food sources, Southern Residents are also dealing with high levels of toxic pollution and increasing vessel noise in their feeding grounds, which makes hunting difficult.

In a particularly dark chapter of the Southern Residents’ modern history, an estimated 48 Southern Resident Killer Whales were removed from the Salish Sea between 1962 and 1977 as part of an aggressive campaign to supply orcas for aquariums. Tokitae, the last surviving orca from this era of capture, sadly passed away in the fall of 2023.

The third group of orcas are the Biggs killer whales, also known as transients, named after the preeminent whale researcher Dr. Michael Bigg. Dr. Bigg was the first western scientist to note that killer whales can be individually identified by their unique saddle patches; dorsal fin shapes; and nicks, scratches and scars. With little appetite for salmon, Biggs are mammal eaters. They are famous for their spectacular hunts and the takedown of the behemoth Steller sea lions, which can weigh 800 to 2,500 pounds. They also eat harbor seals, harbor porpoises, California sea lions, Dall’s porpoises, Pacific white-sided dolphins, and occasionally other whales such as minkes, and juvenile Grey and Humpback whales. Unlike their Southern Resident counterparts who use echolocation to hunt salmon, Biggs hunt in silence. Hunting marine mammals requires stealth and pod coordination.

Why are Biggs orca numbers recovering while Southern Resident orcas decline?

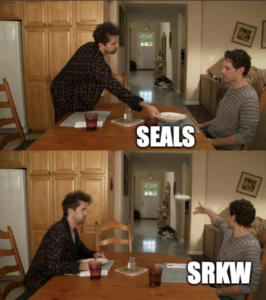

Another difference between the Southern Residents and Biggs is their population density in the Salish Sea. The Southern Residents are listed under the Endangered Species Act, while the Biggs population is on the rise. There are currently around 370 Biggs killer whales, with the population growing 3 or 4 percent annually. Their population has been increasing steadily in the past few decades due to the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Congress passed the Marine Mammal Protection Act in response to increasing concerns among scientists and the public that significant declines in some species of marine mammals were caused by human activities. This created protection not only for the whales, but also the Biggs’ main food sources. As seal and sea lion populations bounced back, the marine mammal-eating orcas were able to thrive. Some Biggs, which have historically inhabited California waters, are showing up more frequently and staying longer in the Salish Sea. Conversely, Southern Residents have been showing up near Monterey Bay more frequently.

While both Biggs and Southern Resident orcas in our region are exposed to high levels of toxics, they are impacted in different ways. Toxic pollution originates from contaminated runoff from roads and developed areas, as well as plastics in our waste stream. These pollutants enter the food chain starting with the smallest creatures, zooplankton. The Zooplankton is in turn consumed by smaller fish, and up up up the food chain it goes — from fish to harbor seal to orca. Along the way the concentration of these chemicals builds in orcas’ body tissue as they eat animals with small amounts of pollutants, a process called biomagnification.

Orcas store these contaminants in their fat reserves over the long term. Biggs’ killer whales are among the most contaminated mammals in the world, with 10 to 20 times more PCBs in their blubber than resident orcas have. These contaminants are fat soluble, meaning they stay locked up in a mammal’s fat reserves, so long as it has a steady source of food.

Unfortunately, low availability of salmon means that Southern Residents’ increasingly rely on their fat reserves, causing the contaminates to leak into their blood streams. This can hurt the health of developing calves. Approximately 69% of Southern Resident pregnancies result in spontaneous abortion. Even if the calf does survive to birth, the mothers continue to offload these toxic chemicals through their milk supply.

The Southern Residents are in peril and need all the help they can get but it’s also important to recognize some positive and ecological wins. Thanks to the Marine Mammal Protection Act, the Biggs population is on the rise and now spotted all year round. Having an ample protected food supply is the key difference between the two populations. There is still hope for the Southern Residents, but only if we double down on efforts to recover salmon runs, slash stormwater pollution, and protect the Salish Sea from risks associated with increased vessel traffic and fossil fuel transport.

Join us in protecting orcas and salmon as we work to build thriving communities that are ecologically functional and restorative.