January through June 2019 was the eighth driest on record for Washington since 1895, with nearly half the state in an official drought emergency following a hot, dry spring and low snowpack in the mountains. Our region has gotten some rain in July and August, which has helped, but haven’t made up for the extremely dry winter and spring — just like a cold snap doesn’t reverse the trend of global heating, a few days of rain doesn’t reverse a drought months in the making.

The term “drought” is thrown around a lot, but to the state of Washington, “drought” means when “the water supply for a geographical area or for a significant portion of a geographical area is below seventy-five percent of normal and the water shortage is likely to create undue hardships for various water uses and users.” (RCW 43.83B.400). The Nooksack River basin was part of the May 20, 2019 drought declaration from Governor Inslee — a stark reminder that the rainy Pacific Northwest is not immune from water worries.

Each year, regardless of official drought declarations, the Nooksack River tributaries become water-scarce in the summer and early fall when rain tapers off and when farms, fish, and people need it most. And this type of drought is likely to become more commonplace as the climate heats up and Whatcom County’s population rises. We need to prioritize solutions like efficient water use in the summer and fall, so a portion of the Nooksack’s water can stay in the streams to keep them cool and flowing for salmon.

Dive into two recent droughts

How is 2019 shaping up compared to the drought declared in 2015, when Washington had another historic drought emergency declaration? Long story short, low streamflows and high water temperatures in our rivers and creeks are not quite as bad as 2015. The Nooksack River and its creeks hit lows in early March of this year, similar to 2015 (see the discharge (flow) graphs below). In 2019, we had a few bouts of rain during the summer, keeping streamflows and water temperatures from being as dangerous.

It’s important to look at several key spots along the Nooksack River to get an overall snapshot of its health. This piece takes a location-by-location look at several years’ worth of streamflow data at five key spots along the river, which are good indicators of how well this year’s flows measure up to the water rights reserved for the river itself (the “instream flow rule” set by the Department of Ecology). That means these spots are also good indicators of how favorable that piece of the river is for spawning salmon. One intriguing finding is that low flows in the Nooksack River at two of these spots, Ferndale and Cedarville, had below-average flows even during the rainy season in 2017 and 2018 for reasons unknown — yet several of its tributaries were normal. Data like this tells us we need to keep an eye on why this is happening and whether it is causing an impact to salmon migrating upstream to spawn.

Read on for a location-by-location look at several years of stream flow at five key spots along the Nooksack River, which give us a snapshot of the health of Whatcom’s most important waterway for salmon, agriculture, and some people’s drinking water.

Want to help balance our water supply in the face of increasing water uncertainty? Email Policy Analyst Karlee Deatherage, karleed@re-sources.org, and see what you can do.

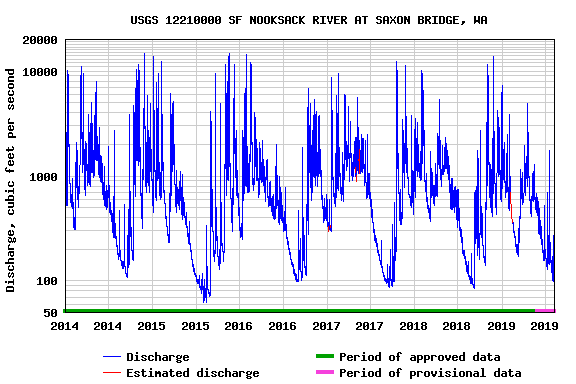

South Fork Nooksack River at Saxon Bridge

The South Fork of the Nooksack River originates west of the Twin Sisters mountain range and flows through the communities of Acme and Van Zandt to meet with the Middle and North Forks in Deming. Unlike the North and Middle Forks, the South Fork fed by snowmelt, natural springs, and groundwater rather than glaciers. It has significant low streamflow and water temperature issues which pose great risk to the many salmon that call the South Fork home.

The South Fork is home to several vital salmon populations: Endangered Species Act (ESA)-listed Spring Chinook, Pink, Coho and Chum salmon and Summer Steelhead. Salmon at this spot:

- Spring chinook (“Threatened” under the ESA) – enters the river beginning in February up until August; spawning in tributaries to the South Fork can begin in July through October

- Pink – enters the river beginning in June or July through September; spawning in tributaries to the South Fork can begin in October through February.

- Coho – enters the river beginning in July up until January; spawning in tributaries to the South Fork can begin in October through February.

- Chum – enters the river beginning in August through January; spawning in tributaries to the South Fork can begin in October and continues through February.

- Summer steelhead – enters the river beginning in April up until October; spawning in tributaries to the South Fork can begin in February through April.

What the flow graphs tell us: Flows are slightly above 2015 low flows, but below normal years. So far, one day has exceeded 70 degrees fahrenheit for water temperature unlike multiple spikes in 2015. Gage height appears to be average.

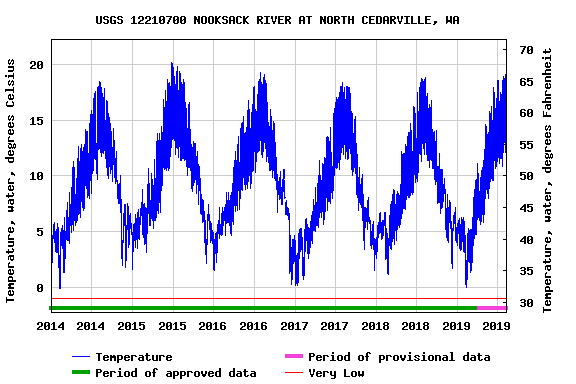

Nooksack River at Cedarville

The Nooksack River at Cedarville is just downstream of where the three forks (North, Middle, and South) converge just outside of Nugent’s Corner. Flows and depth are pretty significant. Most salmon and steelhead don’t spawn here as they’re making their way to certain tributaries of the three forks; however, Chum salmon occasionally spawn in the mainstem Nooksack. Salmon at this spot:

- Chum – enters the river beginning in August through January; spawning in the mainstem can begin in October and continue through February.

What the flow graphs tell us: Flows, temperature, and gage height are fairly average for this time of year.

Fish Trap Creek at Front Street, Lynden

Fish Trap Creek originates in lowland British Columbia, south of the Fraser River and makes it way through farmland and the City of Lynden and enters the Nooksack just southwest of town, just upstream of Bertrand Creek. Fishtrap Creek often faces challenges with high water temperatures and low streamflows. Salmon at this spot:

- Chum – enters the river beginning in August through January; spawning in Fishtrap can begin in October and continues through February.

What the flow graphs tell us: Flows, temperature, and gage height are fairly average for this time of year. Flows and gage height in late July and early August 2015 were slightly better than 2019.

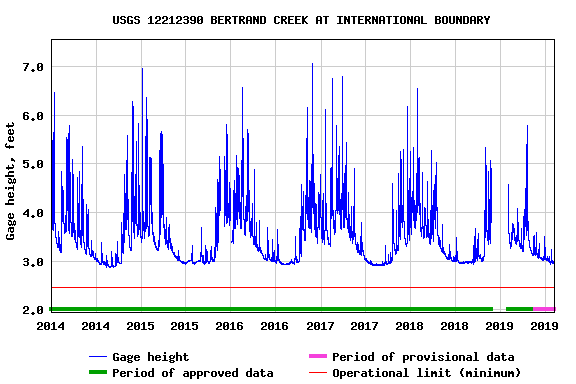

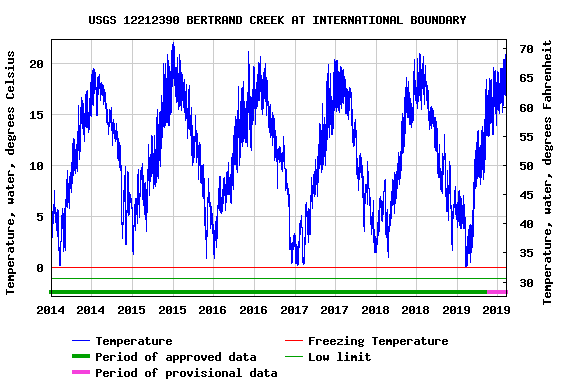

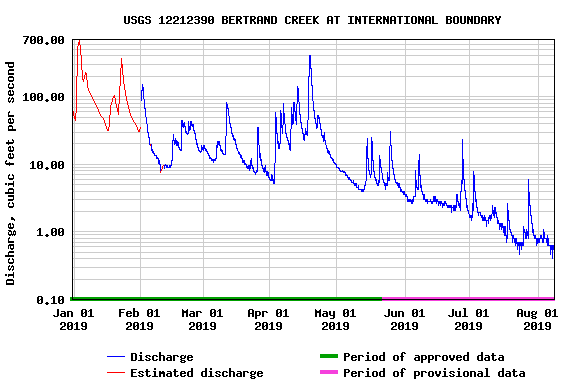

Bertrand Creek at International Boundary

Bertrand Creek originates in lowland British Columbia, south of the Fraser River and makes it way through farmland and enters the mainstem Nooksack River just west of the confluence of Fishtrap Creek. Like Fishtrap Creek, Bertrand Creek has serious problems with high water temperatures and low streamflows. Salmon at this spot:

- Chum – enters the river beginning in August through January; spawning in Bertrand can begin in October and continues through February.

What the flow graphs tell us: Gage height and temperature are fairly average for this time of year. Flows are below average years, but above the 2015 low flows.

Mainstem Nooksack River at Ferndale

The mainstem Nooksack River at Ferndale is essentially the “salmon highway” (for spring and fall Chinook, pink, coho, and chum; plus winter and summer steelhead). Spawning does not typically take place here. Temperature and streamflows are typically not a concern; however, water temperatures were close to lethal (above the 20 degree celsius mark) for salmon a handful of days in 2015.

What the flow graphs tell us: Flows and gage height are slightly above average this time of year over the last 5 years; however, temperature appears to be creeping above the 5 year average yet below the 2015 water temperature highs.

Sources:

- Nooksack River salmon species populations: https://fortress.wa.gov/dfw/score/score/maps/map_details.jsp?geocode=wria&geoarea=WRIA01_Nooksack

- Salmon life stages in the Nooksack River: http://salmonwria1.org/webfm_send/27

- Nooksack River Instream Flow Rule (Rule): https://fortress.wa.gov/ecy/publications/publications/0010046.pdf

- US Geological Survey, Nooksack River Stream Gages: https://waterdata.usgs.gov/wa/nwis/current/?type=nooksack&group_key=NONE

- Lethal water temperatures for salmon: https://fortress.wa.gov/ecy/publications/publications/0010046.pdfDrought 2019: https://ecology.wa.gov/Water-Shorelines/Water-supply/Water-availability/Statewide-conditions/Drought-2019